The Relevance of Meaning in Palliative Care

January 10, 2026

According to a well-known anecdote, the famous anthropologist Margaret Mead was once asked by a group of students, “When did civilization start?” Some speculated that her answer would be along the lines of “When humans learned how to use fire,” or “When humans invented the wheel,” or “When humans began to communicate,” invented writing, etc. To their surprise, Mead observed a broken and healed human femur, the long bone that connects the hip with the knee, and replied, “Helping someone else through difficulty is when civilization starts.” (1)

She explained that wounded animals in nature would not have a chance to live. They would be left to die, ostracized, or eaten by others before their bones could heal. A healed femur is a sign that an individual has received help from others. That is, they were not abandoned, left to die alone, discarded, or disregarded. They were probably taken to a safe place and given water to drink and nutritious food to eat. Ointments, bandages, or supports were most likely used while allowing the injured person to rest and recuperate until the bone heals.

Many have argued vehemently against the validity of this claim on many accounts. (1) One of them was that Margaret Mead may have never said these words. (1) Others have noted that altruistic actions are not unique to humans; they can be found in other species. Elephants care for their young, chimpanzees have been observed treating each other’s wounds with insects. Regardless, one thing we may establish for sure: the way a society treats its most vulnerable members is a telling sign about its priorities and values.

The hospice movement is based on the altruistic motivation to care for those who, because of age or illness, require a space where they are cared for by competent professionals, allowing them to live their final months or days in peace and comfort. (2) It is based on the assumption that each individual has unconditional dignity which is inherent in their personhood. (2)

Palliative care grew out of the hospice movement, and it “…offers specialized medical care for people with serious illness focused on proving patients with relief from the symptoms…that accompany the illness, regardless of the prognosis…to improve the quality of life for the patient and his or her family.” (3)

Surprisingly, or perhaps not surprisingly, the roots of compassionate care for the sick and dying go back thousands of years. The Latin word “hospitium,” meaning hospitality or guesthouse was used already in 300 A.D. It referred to shelters by the roadside that were erected to serve as resting stops for travelers. (4) Such shelters have been established since ancient times along major pilgrimage routes. They were not hospitals for the “curing” of diseases but places of rest for injured or dying travelers. (5)

In ancient times, soldiers were often prioritized for receiving medical care over civilians. The aim was to restore them to being fit to fight rather than provide end-of-life care. (6)

In the fourth century, a Roman noble woman, Fabiola, was the first noted example of someone who established a home for the destitute and poor. She was guided by Christian values and provided generously for the care and comfort of the sick and dying. (4)

Monastic care surged in the Middle Ages and the concept of “hospice” became formalized through the work of religious orders dedicated to the care of the sick and dying. Monasteries for centuries have become the place where people who sought medical care and spiritual care gravitated because here, through the dedication of the nuns, monks, and lay religious, they were treated with respect, and where death was seen as part of a transition into eternal life rather than a medical failure that needed to be fixed. (7)

In 1443, in Beaune, France, Nicholas Roulin founded a “Palace for the Poor,” which he called l’Hotel-dieu or God’s Hotel. (8) It was a beautiful, architecturally pleasing building with the intention of reinforcing the worth and dignity of those close to the end of their lives. It was built over a river with glass windows to the water under each of the patients’ beds. Over their beds, on the ceiling it was written in Latin, “Ars sacra moriendi, ars sacra vivendi.” –The sacred art of dying is the sacred art of living. (8) Nicholas Roulin wrote, “The only measure of society’s greatness depends upon how it cares for the poorest of its poor at the end of life.” (9)

During the next several centuries, medicine made significant advancements in identifying types of diseases, classifying them, and developing ways of treating them. “Curing” diseases shifted the emphasis of most practitioners to wanting to be in position of influence and to gain the expertise and knowledge required to do so. In the meanwhile, poor and marginalized people were often disregarded. Religious institution and charities such as the Dames du Calvarie in Lyon, France, established in the 1840s, and Our Lady’s Hospice in Dublin, Ireland, established in 1879, sought to provide for the needs of the terminally ill and the dying. (10, 11)

The transition from charities and religious institutions as the only places where care for the terminally ill was provided, to hospices, where medical innovations were applied to the care of the terminally ill, took place in the 1960s. Dame Cicely Saunders, greatly inspired by the work of Dr. Viktor Frankl, established the first modern hospice, which was to be the forerunner of modern palliative care hospitals and institutions. (12)

During her studies in the 1940s and the 1950s, Dame Cicely Saunders noticed that the predominant approach to the care of the terminally ill patients was deficient in two crucial aspects. First, it did not consider the spiritual aspirations of the dying. Second, it did not apply the knowledge that was already available about the alleviation of pain in the palliative setting. (13) Under spiritual aspirations, Dame Cicely considered existential issues as well as deep seated spiritual longing for a sense of wholeness and completion. (13) She also noted that doctors often “left,” as if “abandoned,” their terminally ill patients who experienced excruciating pain and paralyzing sense fear and anxiety:

“I thought it so strange. Nobody wants to look at me. “

“Will you turn me out if I can’t get better?” (36)

Under such conditions, their physical pain interfered with their ability to be fully present and to have a sense of mastery over their own process of death. (13, 36) The existential issues concerned her, because she noticed that when pain medication was provided, and patients were able to regain their serenity, oftentimes they expressed strong feelings of fear or resentment about their condition or their impending death. Ignoring such feelings fueled a sense of hopelessness. She wanted to reverse this tendency and acknowledge people’s feelings and help them express it in order to engage in a process of finding a response together that would help her patients die in peace. (13)

In the book, “The Psychiatrist and the Dying Patient,” (1955), Dr. Kurt Eissler, a psychoanalyst follows the dying process of a forty-year-old mother of two young children. This lady had been active taking care of her children until the time she was diagnosed with terminal cancer and required hospitalization. The psychiatrist, Dr. Eissler, spent many hours talking with her. Invariably, during such conversations the question of the meaning of her life surfaced. She said that she perceived her life meaningful before the cancer diagnosis, while she was with her family, but not ever since, because she could no longer take care of her children and was bedridden. In one of the conversations, Dr. Eissler told her that any of such observations about the meaning of life are mistaken and that she should not be concerned with such questions anymore. Upon hearing this, she became tearful, confused, and did not know what to say. She became withdrawn, albeit remained polite toward the doctor and thanked him every time the pain medication was administered. Once, she requested to see her family, but this request was denied. Dr. Eissler reported that she died in a stoic way, accepting her suffering. (14)

Around the same time, Dame Cicely heard another account of an elderly lady being treated by a psychiatrist. Her fictional name was Ms. Kotek. (15, 21, 25, 26) She was diagnosed with terminal cancer, and she expressed sadness to the point of depression that her life will end. She had been a maid in the service of a wealthy family, and she had come to the attention of Dr. Frankl, who led her through a long conversation about her life. Upon the remark that all this will end now, they noticed together the wonderful and beautiful events that Ms. Kotek experienced and the suffering that she shouldered with courage. Frankl noted that these peak experiences and accomplishments no one and nothing can remove from the face of the earth. He congratulated Ms. Kotek for her exemplary attitude and at this conversation, she beamed with a sense of pride. “My life was not in vain,” she said to herself, “My life is a monument,” she repeated what Frankl had said. Dr. Frankl reported that she died peacefully, and not with a sense of being dejected. Her last words were, “My life was not in vain.” (15:98)

Dame Cicely was immediately taken by Frankl’s presentation and wanted to know more about logotherapy. In Logotherapy, she found what she was looking for: a way of addressing questions of meaning that help to ease the existential distress of those who are dying or close to death. (16)

This year in 2026, one hundred years have passed since 1926, when Viktor Emil Frankl, MD, PhD (26 March 1905 – 2 September 1997), a young medical doctor at the time, held a presentation at the Medical Society of Vienna and he used the term “logotherapy” for the first time. (16, 21, 25, 26) It referred to a meaning-centered and holistic approach to the care of people suffering from various forms of illness. Central to his theory was a three-dimensional view of the person as a body, mind and spirit entity, which, at the time, was in sharp contrast with the predominantly psychoanalytic view adopted in the care of sick and suffering people. (18)

Frankl claimed that each person’s essence is their indomitable and unscathed spirit, which he conceptualized as a dynamic rather than an entity limited by time and space. The dynamics of the human spirit, according to Frankl, is active and potent in the form of the “Will to Meaning.” This is a fundamental human motivating force, more relevant than the will to power or the will to pleasure, that is oriented toward the reason and ground of existence, which he called meaning, or with a Greek word, Logos. (18)

Frankl illustrated the capacities of the human spirit for self-distancing, observing oneself and one’s circumstances from the outside, and self-transcendence, the ability of reaching toward values. He outlined three avenues through which meaning can be found, such as through creative, experiential, and attitudinal values. Creative values are what we give to the world that was not there before. Experiences are what we take from the world such as experiences and encounters. Attitudinal values are at play when we decide on the position that we take toward a situation that cannot be changed. (18)

Frankl asserted that a human being is free to take a position toward themselves and toward the challenges and difficulties that confront them. He termed this capacity the defiant power of the human spirit and asserted that human beings at any moment are free to change and mold themselves to become the values they adopt; while we are conditioned by bio-psycho-social forces, we are not determined by them. (19) Challenges and crises intensify the question of meaning, which people have the capacity to answer because in the dimension of spirit, they retain an area of freedom and responsibility. Through their conscience, a resource of the human spirit, they can discern the best possible answer among many alternatives. (19)

Frankl proposed that there is a type of suffering, the existential vacuum, which results from not seeing meaning in life, and this is a type of existential suffering, which is not necessarily pathological, as it was seen by Freud and Adler. On the contrary, questions of meaning are a sign of true humanity. (18) They propel the search for meaning. However, when questions of meaning are ignored, denied, or suppressed, they lead to the intensification of the symptomatology and lead to distress. Distress may lead to despair and despair may intensify the symptoms of anxiety and depression. Frankl spoke of a “Noogenic neurosis” which does not originate in the past but in the present, exactly because of not seeing meaning in life. (19:115) He developed Logotherapy and Existential Analysis specifically to help people find meaning and prevent and protect against despair. (18)

Since he was Jewish, Frankl, was deported to the concentration camps During the Second World War. There, he, like the other prisoners, suffered indescribable humiliations and faced the possibility of death. He put his theories to use and linked his fate with the possibility of finding meaning in suffering: he encouraged others and put his medical knowledge at the service of the other inmates. Other times, he attempted to distance himself from the conditions by contemplating the image of his loved ones and envisioning teaching others about what he learned from his experiences in the camps. (18, 20)

Freudian psychotherapists predicted that if people are subjected to such brutal conditions, they will all behave the same way and fight for their survival by becoming hostile toward each other. Frankl, who was in the camps, observed the opposite: “Life in a concentration camp tore open the human soul and exposed its depths.” (18:81) There were those who chose, in this situation, to share their last piece of bread, or to enter the crematoria with a prayer on their lips. (18)

Frankl emerged from the camps with the firm conviction that human beings do not simply exist but always decide what their existence will be, what they will become in the next moment. (18). Finding meaning is possible in the face of pain, guilt, and death, the tragic triad of suffering, which is an indelible part of life. Through self-transcendence, people are able to turn suffering into a lasting human achievement. (18)

In the post war period, Frankl continued to refine the principles and methods of Logotherapy and Existential Analysis and sought to incorporate both experiential examples and scientific findings about the relevance of meaning in crisis prevention and crisis intervention. From 1940 to 1942, he was head of the Neurology Department of the Rotschild Hospital, and between 1946 and 1970 he was Director of the Vienna Neurologic Policlinic. (20, 21) Since 1954, he travelled internationally, first to England, the Netherlands and Argentina, then the United States and Canada and many other countries of the world, where he held lectures about logotherapy and existential analysis, which school of psychotherapy increasingly became known as “The Third Viennese School of Psychotherapy,” after Freud’s Psychoanalysis and Adler’s Individual Psychology. (21)

In 1955, he was promoted to Professor at the University of Vienna. (21) Since 1954, Professor Gordon Allport at Harvard University promoted logotherapy and at his insistence, Dr. Frankl’s most well-known book, “Man’s Search for Meaning” was published for the first time in English translation in 1959. (20, 21) Dr. Frankl held professorships at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, The University of Pittsburgh, the University of Dallas, Texas, and the U.S. International University in San Diego, California. (21)

He authored forty books which to date have been translated and published in close to sixty languages. (21) He was awarded several prestigious awards among them the Albert Schweitzer Medal, the Oskar Pfister Award of the American Psychiatric Association, and Lifetime Achievement Award of the Foundation for Hospice and Homecare. (21) In addition, he held twenty-nine honorary doctorates from universities around the world. (21) His legacy is carried on by the Viktor Frankl Institute Vienna, The International Association of Logotherapy and Existential Analysis, and a network of accredited institutes and associations dedicated to the practice and teaching of logotherapy world-wide.

Dame Cicely Mary Strode Saunders (22 June 1918-14 July 2005) incorporated the principles of Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy and existential analysis into her philosophy of care. (22,26) She is internationally recognized as the founder of the modern hospice movement, and she is credited for establishing the discipline and the culture of palliative care. (22) Through her life, Dame Cicely Saunders held the life-affirming view that with the alleviation of pain and providing support, the suffering of terminally ill patients can be reduced, and their quality of life can be improved, so that they can live their last days to the fullest. (16, 22)

Hospice care provides caring and compassionate care for people in their last phases of incurable disease or aging so that they may live as fully and comfortably as possible. It prioritizes improving the quality of life through reducing pain and addressing the sadness and suffering that people often experience related to parting and providing support and choices for the individual and family members so that they can be fully present. It is based on a life-affirming philosophy which does not try to hasten or postpone death. (22, 23)

Care is provided by an interdisciplinary team that works for the best interest of the patient in terms of their physical, emotional, and spiritual needs, and it usually consists of a doctor, nurses, counsellor or therapist, social worker, chaplain, occupational and physical therapist, home health aides and trained volunteers. Their primary responsibility is to manage pain and symptoms, provide emotional support, provide medications and equipment, coach caregivers on how to care for the patient, deliver special services, such as speech and physical therapy when needed, and offer bereavement support. (22, 23)

If the philosophy of a hospice could be summarized in one sentence, it would be the one by Dame Cicely Saunders, the founder of the first modern hospice,

“You matter because of who you are. You matter to the last moment of your life, and we will do all we can, not only to help you die peacefully, but also to live until you die.” (22)

Dame Cicely Saunders was born in Barnet, Hertfordshire, England as the eldest daughter of Philip Gordon Saunders and Mary Christian Knight. (23) In her youth, she studied politics, philosophy and economics. In 1938, she enrolled to a nursing program at Nightingale School of Nursing based at St. Thomas Hospital. (23)

After suffering a back injury which forced her to take frequent breaks, she decided to continue her studies at St. Anne’s College, and earn her BA degree, qualifying as a medical social worker. It was during this time that she cared for a dying Polish Jewish immigrant who escaped from the Warsaw Ghetto, David Tasma, who was dying of cancer. He felt that his life had become worthless. Cicely spent a lot of time with him, discussing various topics such as faith, religion, and life’s meaning. David managed to regain his faith and required less pain medication towards the end of his life. She shared with him her dreams of one day, opening a home where dying people would be able to find peace in their final days. When Tasma passed on, he left her a sum of money with the note, “I’ll be a window in your home.” (24)

After Tasma’s death, she experienced complicated grief, however, she was convinced that she now understood what she has been called to do. Aged 33, she was accepted at St. Thomas’s Hospital Medical School where she trained and graduated as a doctor in 1957. Subsequently, she enrolled to St. Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, to study pain management, and worked at two hospices where she used her medical knowledge and research findings to improve the standard of care. By 1959, she had drawn up a ten-page proposal for her hospice. (24)

The construction of St. Christopher’s Hospice began in 1965, and its doors opened in 1967. The hospice contained 54 beds. It served a s a model of excellence in care for similar centers in England and abroad. It soon extended its activities to research and study of pain management and meaning-centered principles in the care of terminally ill patients. (24)

Dame Cicely Saunders was medical director of St. Christopher’s Hospice from 1967 until 1985. She produced prolific writing and correspondence as her work was noticed and acclaimed both nationally and internationally. The National Health System of England incorporated her principles into their ethos and designated her center as one of the training institutes for nurses. She died from breast cancer on the 14th of July 2005, having spent her last days at her beloved St. Christopher’s Hospice. (24)

Several merits and honors were bestowed upon Dame Cicely Saunders. In 1977, she was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Archbishop of Canterbury and honored with the title, Dame of the Order of St Gregory the Great by the Pope. In 1979, she was appointed Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. In 1981, she received the Tempelton Prize. In 2001, she was the recipient of the Conrad N. Hilton Humanitarian Prize. (24)

In 2003, Dame Cicely Saunders received the Honorary Prize of the Viktor Frankl Institute, Vienna, for her outstanding achievements in the field of meaning-centered humanistic psychotherapy. (25)

Dame Cicely Saunders was introduced to logotherapy as early as in the 1950s by Professor Gordon Allport. He was a contact through her brother, Christopher; he was Chair of Psychology at Harvard University and Executive Secretary of the Ella Lyman Cabot Trust, which supported the visit of Dr. Cicely Saunders to the United States. (21, 26)

In 1961, Professor Gordon Allport had invited Dr. Viktor Frankl to the United States for a lecture tour at Harvard University, which was followed by lectures tours and presentations at other major universities in the United States, Canada, and other countries of the world. (21, 28) Professor Allport coordinated the translation and publication of Frankl’s first book to appear in English translation, “Man’s Search for Meaning.” Gordon Allport was the first who introduced Dame Cicely to the writings of Dr. Viktor Frankl, which proved to be highly inspirational upon her thinking in the following years. (26)

Dr. Frankl’s influence is evident in Dame Cicely’s thoughts and writings. Based on Frankl’s three-dimensional view of the person as body, mind and spirit entity, Dame Cicely introduced the notion of “total pain,” including physical, emotional, social and spiritual pain; the latter being a suffering related to not seeing meaning in life. Her article on “spiritual pain” explains that toward the end of life, “…there may be bitter anger at the unfairness of what is happening, and at much of what has gone before, and above all a desolate feeling of meaninglessness. Here lies, I believe the essence of spiritual pain.” (27)

Dame Cicely shared Frankl’s view that the will to meaning is the most important motivating force and that the impulse to find meaning is intensified in difficult situations. She stated that, “Coming to terms with loss intensifies the ever-present search for meaning.” (16) Furthermore, she believed that people have the capacity to manage their dying process when avoidable suffering is alleviated. They can discover meaning in the unavoidable aspects of their suffering if they are given the proper care and support. (16)

Inspired by Frankl’s lectures and books, according to which “…even the helpless victim of a hopeless situation, facing the fate he cannot change, may rise above himself, may grow beyond himself, and by doing so, change himself. He may turn a personal tragedy into a triumph” (Frankl, 18:147), she was convinced that every person can find meaning in suffering. (16) This was relevant especially in end-of-life care, where people required adequate care and support to bring their life’s tasks to completion in peace. (16)

Dame Cicely’s concept of “watching with” is similar to Frankl’s notion of being present and “being with” the suffering person.

“The same words ‘Watch with me’ reminds us also that we have not begun to see their meaning until we have some awareness of Christ’s presence both in the patient and in the watcher. We will remember his oneness with all sufferers, for what is true for all time whether they recognise it here or not. As we watch them we know that he has been here, that he still is here and that his presence is redemptive.” (29: 5)

Like Frankl, Dame Cicely believed in administering the right medications at the right time and in the right dose in order to help patients to experience consciously the last stages of life. (Her goal was to present her scientific findings to update medicine on the use of morphine and diamorphine during palliative sedation which allowed patients to process negative feelings and emotions rather than avoid them.

“Sadness is appropriate and should be faced and shared. It calls for a listener, rather than for drugs, although the combination of the two may help to lift an inhibiting load and enable a patient to tackle problems that had seemed unmanageable. When such treatment is carefully assessed and reviewed, this is not to manipulate the mind but to give it greater freedom and strength in facing reality.” (29:21)

The dying process, according to Dame Cicely, is a natural part of life. The moment of death, like in Frankl’s work, is the instance of separation of the spirit from its instruments, the body and the mind. It is a spiritual achievement of having reached completion and the fulfillment of what was meant to be accomplished in this life. (30)

“The lesser her body could do the more her spirit shone, in love and amusement and a clearsighted wisdom concerning life and those she met. Body and mind are linked indissolubly but they are of much less account than the spirit whose purposes they serve. That is not only unique and irreplaceable; it is also indestructible, stronger even than the light energy of the star which streams across the universe millions of years after its source has ceased to exist.” (30:2-3)

Comparing these lines with Frankl’s statement, “What we ‘radiate’ into the world, the ‘waves’ that emanate from our being, that is what will remain of us when our being itself has long since passed away” (31:45), we can see that Dame Cicely’s thoughts dovetail Frankl’s. Frankl’s “Ten Theses on the Person” are mirrored in Dame Cicely’s view of the body and mind as the instruments of the unscathed human spirit, which transcends the constraints of time and space (32, 33).

Dame Cicely was familiar with the basic principles and tenets of logotherapy. In her accounts, she illustrated how finding meaning was part of a journey and an accomplishment. From self-awareness, the journey led to self-discovery, and the discovery of the resources of the human spirit to find meaning through an authentic and self-transcendent way of living. (16, 27, 29, 30, 35, 36)

“The modern hospice is a resting place for travelers but above all it is concerned with journeys of discovery. For patients, a discovery of what is most lasting and important for them as they unravel some knots of deceit and regret.” (34:61)

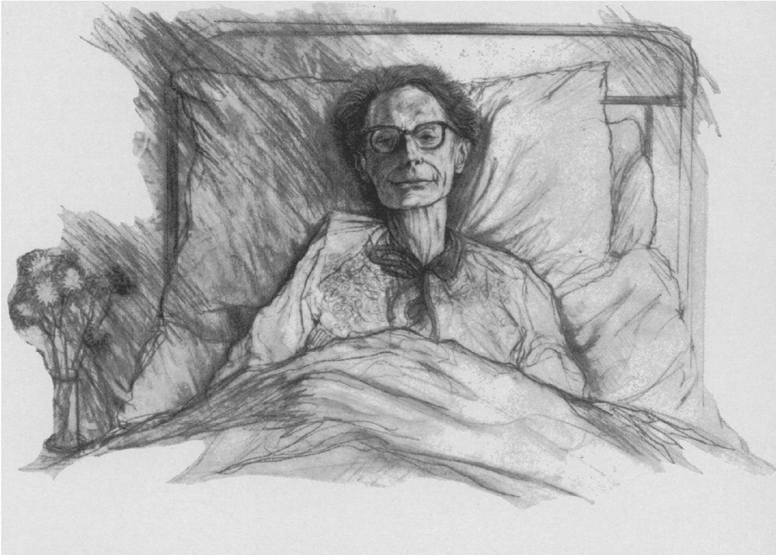

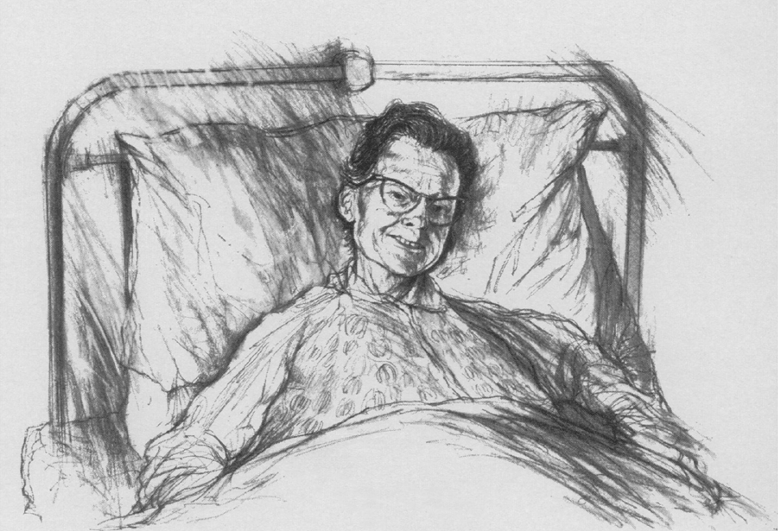

Dame Cicely believed that artistic creations such as drawings, sketches, and photographs helped people track their journey, and helped them to express themselves in ways that did not require words but allowed for the communication of their feelings and emotions. She believed that, while science aimed at observing and noting generalities, art was the expression of individuality and could be used to help people communicate about their unique journey. She often made use of drawings and photographs to document the work of the hospice. She published numerous accounts of her patients reaching closure and completeness and portraying calmness and serenity (16, 24).

The above drawings by an unknown artist demonstrate the change in the expression of a patient. Dr. Saunders explains, “Treatment is such …[at the hospice] that, although near death, these patients–sketched from photographs taken just a few days before they died–were free from anxiety and pain; their faces mirror their peace in their last stages of life.” (36).

Since Dame Cicely’s pioneering work at St. Christopher’s Hospice, the medical and the nursing professions have paid close attention to the role of meaning in alleviating suffering. (24, 36) Her research coincided with the results of others that showed that meaning has a preventive and curative value and finding meaning in suffering has a salutogenic effect. (12, 36) Her work is carried on by several centres of excellence in the United Kingdom and abroad. (13, 24, 35)

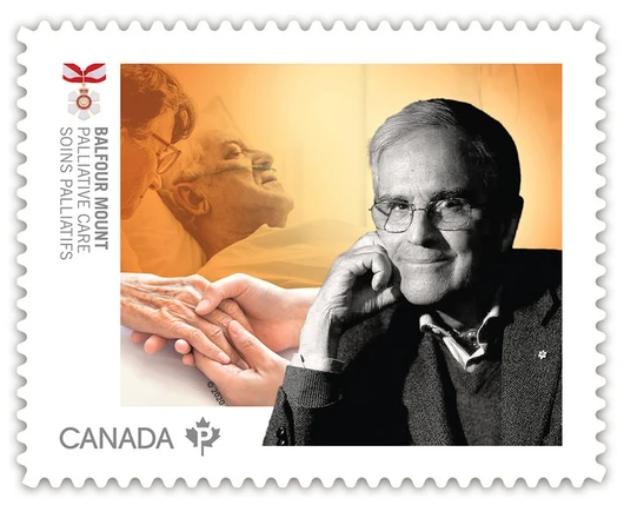

In Canada, “The Father of palliative care in North America,” Dr. Balfour Mount, (1939-2025) frequently and devotedly referred to Dame Cicely and quoted her work. (39) Dr. Balfour Mount had the privilege of visiting Dame Cicely at St. Christopher’s and learning from her first-hand. Until the very last days of his life, he continued to be “deeply committed to palliative care, has been instrumental in the establishment of palliative care services, research and teaching in Canada.” (37)

He recalled the first time she met Cicely Saunders:

“I heard of St. Christopher’s Hospice in London through Elisabeth Kübler Ross book, ‘On Death and Dying,’ published in 1970. We had done our study at the Royal Victoria Hospital, and I knew we had a problem. In my report to the Board of the Vic, I wanted to make some suggestions on how care could be improved, so I phoned Dr. Saunders at St. Christopher’s Hospice. After telling her who I was, I said, ‘Could I come for a visit?’ And she said, ‘I could not possibly consider that now, I am on my way to lunch. Call me in an hour!’ Click! So, I called back and she said, ‘I know you. You want to come to London with your wife, see a few plays, have a quick look around the hospice and go home. Well, I won’t have it! I’ll tell you what, leave your wife at home, be prepared to stay for a week, role up your sleeves up and work hard, and I’ll have you.’ That’s when I fell in love with Cicely. I visited in the second week of September 1973. I was deeply impressed by St. Christopher’s, by Cicely, Mary Banes, Terese Vanier, Tom West and the galaxy of superstars she had assembled, including the wonderful nursing staff.” (37)

Dr. Balfour Mount described Dr. Cicely as “…a strong leader, a clear thinker, discerning, with a good sense of humor.” (37) She left a lasting impact on his personal and professional formation.

“I have been writing a book for a number of years and just this morning I wrote about Cicely Saunders’ death. What it means to me is having had the privilege of being a devoted disciple of Saint Cicely. I called her that once in a meeting and has come up to me afterward and said, ‘Oh, incidentally, if you ever call me Saint Cicely gain in public, I shall kill you!’ She was wonderful! I think the international community owes her a great deal for having transformed healthcare around the world. I am so grateful for having known her.” (37)

Dr. Balfour Mount was also devoted to the work of Dr. Frankl, and participated in the screening of the short movie, “Frankl’s Choice” produced by Ruth Yorkin Drazen (2014). In this video, he gave firsthand account of his use of logotherapeutic principles in the palliative care setting. (38) Reflecting on the sad state of legislation in Canada legalizing euthanasia without as of yet, respect for the conscience right of doctors, Dr. Balfour Mount stated:

“The suffering of people at the end of life has been enough to legalize euthanasia and physician assisted suicide but interestingly, not enough to mandate excellence in palliative care for all Canadians. This is an ongoing need and, in my view, a tragedy.” (37)

In Australia, Professor Ian Maddocks held the First Chair at Flinders University, the first President of the Australian Association for Hospice and Palliative Care, and First President of the Australian and New Zealand Society for Palliative Medicine. He considered Dame Cicely Saunders an important mentor in the field of palliative care. (41)

“It must have been soon after I had the chair, because I remember the Dame [Cicely Saunders at St. Christopher’s] looking down her nose at me thinking: who’s this upstart from Australia who’s got a chair? Who is he? Never heard of him! [Chuckles]. What impressed me the most about her was her persistence and vision. She knew as a young nurse what she wanted to do and sustained that through further training in social work and in medicine over decades. She was an important example and mentor to many.” (41)

One of those who consider Dame Cicely as an important example and mentor is Dr. Christopher S. E. Wurm, Senior Consultant in Primary Care, and Specialist in Addiction Medicine, Visiting Fellow in the Discipline of Psychiatry at the University of Adelaide. (42) He first came across the work of Viktor Frankl while still in medical school in the 1970’s, and he was instantly attracted to the work of Dame Cicely Saunders and Professor Balfour Mount who acknowledged Frankl’s influence on the evolution of Palliative Care.

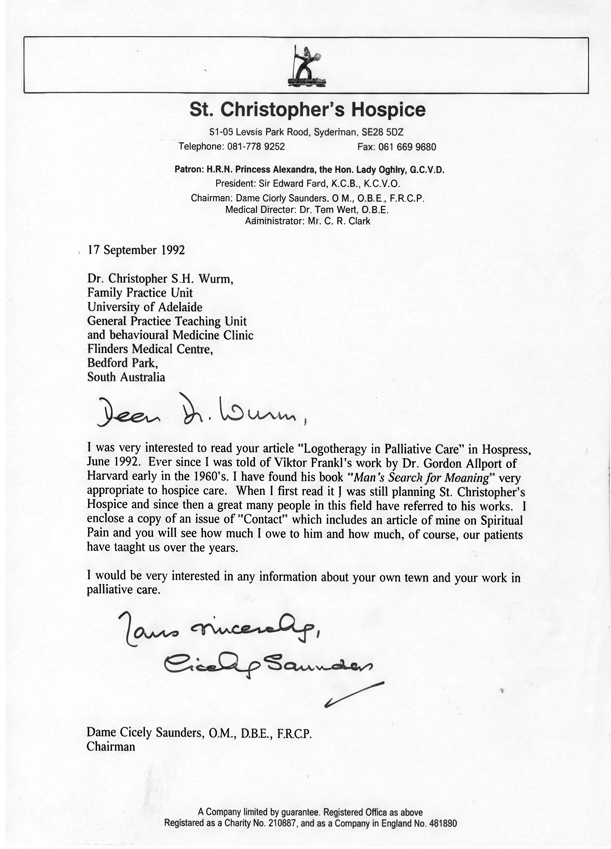

In 1992, Dr. Wurm wrote an article with the title, “Logotherapy in Palliative Care,” in which he highlighted the relevance of the use of logotherapy in the palliative setting based on his experience as a medical doctor. (42)

Dame Cicely read the article. Unexpectedly, and to Dr. Wurm’s great surprise, she sent a letter to acknowledge her interest in the article. In this letter, she confirmed the significant impact of Dr. Viktor Frankl on her work since the 1950s, thanks to Professor Dr. Gordon Allport. (43)

With this letter, Dame Cicely sent a copy of her article on “Spiritual Pain” to Dr. Wurm. This article contains her presentation on the occasion of the Fourth International Conference, held at St. Christopher’s Hospice in September 1987. (27, 40, 44)

In this article, she highlighted the ways in which Frankl’s “Man’s Search for Meaning” has given hope to many of the people who they helped. She spoke about the challenges, the achievement, and the limits of what can be achieved in palliative care, and she closed her speech with the following thoughts:

“Our own pain will be easier to bear if we can hand on quietly what we have been given and hope that it will be used and, in our turn, continue our own search for meaning, for acceptance of our own story, and our place in a creation that is ultimately good and to be trusted.” (27, 40, 44)

In 1980, Dr. Balfour Mount organised a conference on palliative care at the Victoria Hospital in Montreal and invited Dame Cicely Saunders and Dr. Viktor Frankl as keynote speakers. (25, 26) Years later, in 1993, Dame Cicely thanked Dr. Frankl for his insights and for his influence on the hospice movement in a letter stating:

“I had the pleasure of listening to you at the Montreal Conference a number of years ago now. I am sure, many people in the hospice world have thanked you for your influence on our thinking, but I would like to add my voice once again.” (45)

She has come “full circle,” as she would have observed. She thanked those who lit her torch and she handed in over to the new generation of doctors, nurses, chaplains, and therapists. The world will never be the same without Dame Cicely Saunders, but we learned important lessons from her. These lessons do not pass away. (46, 47, 48)

Current research upholds the role of meaning in the alleviation of suffering. For example, a recently conducted MRI study with twenty-nine participants found that the ventromedial prefrontal cortex is activated when suffering is associated with meaning, such as accepting suffering in order to reduce the suffering of a loved one. (49) A study on young adult and middle-aged terminal cancer patients showed that meaning-centered intervention reduced measurable levels of suffering and improved quality of life, even when the underlying physical illness remained. (50)

“In general, studies have shown that cancer patients who experience high degree of meaning have a greater ability to tolerate bodily ailments than those who do not find meaning in life. Those who, despite pain and fatigue, experience meaning, report better quality of life than those with low meaning. Therefore, meaning is considered a vital, salutogenic resource.” (51, 52)

In the United Sates, a ground-breaking series of randomized control trials with an eight-session meaning-centered intervention was conducted under the direction of Dr. William Breitbart at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Treatment Center Hospital in New York. The sessions incorporated logotherapeutic principles and were aimed at reducing depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, among patients who have been diagnosed with advanced stages of cancer. As compared with those patients who received Supportive Psychotherapy and Enhanced Health, those who participated in the meaning-centered group showed improved quality of life and sense of meaning and less anxiety and desire for a hastened death. (53, 54, 55) The standardized treatment manuals were published for individual and group therapy applications. (56,57)

In collaboration with Breitbart’s team, several researchers in Canada’s Laval and McGill Universities in Quebec, as well as York University in Ontario, have started initiatives of enhancing palliative care practices by incorporating logotherapeutic principles into the training of practitioners and the delivery of care (58, 59, 60). This work is promising and currently ongoing.

Like the late Prof. Dr. Viktor Frankl, Dame Cicely Saunders, and Prof. Dr. Balfour Mount, those who follow in the footsteps of the pioneers of modern palliative care are convinced that as suffering belongs to life, its meaning is always related to the perception of life’s meaningfulness. When unnecessary pain is alleviated and people receive care that recognizes their search for meaning, they can complete their life’s project in peace and with serenity.

Meaning serves as a powerful protection against depression, hopelessness, and a desire for hastened death. Meaning-centered interventions significantly increase spiritual well-being and quality of life compared to traditional group therapies.

The challenge remains to shape current world view to see value in reaching out to those who are most vulnerable, and to find it worthwhile to help people who are terminally ill or dying live to the fullest up to their last breath.

Human beings require considerable amount of care. A human infant stays in the womb for nine months, after which they require physical and emotional care to remain alive, to contribute to the optimal development of the brain, and for acquiring skills and learning how to function in a complex society. A basic attitude of acceptance, nurturing, and loving care—the experience of being wanted and protected—fosters a child’s sense of trust and belonging. Benefiting from a nurturing and safe encounter with their surroundings, children can continue to mature, acquire developmental milestones, and increasingly acquire the skills to function in a complex and demanding environment. The capacities of the human spirit, which are dormant in the early stages of life, are thus increasingly awakened and can express themselves through their instruments, the body and the mind. (61)

As a human being grows and develops, they are increasingly able to rely on their inner resources, such as the resources of the human spirit, which make human beings unique. In the process of maturation, a human being becomes increasingly more able to have more independence–gain freedom and identify areas of freedom; discern right from wrong and decide to act one way or another which is the root of morality and responsibility; and to increasingly become capable of discerning what is worthwhile to strive for–what is meaningful and what values one chooses to actualize. The capacity to creatively shape oneself and one’s environment; the ability to relate to oneself, others, and the world of values; and to choose a position or an attitude toward internal and external circumstances is a unique prerogative of human beings.

Throughout lifespan, these abilities to actualize creative, experiential, and attitudinal values play various roles at different times. They form part of the essence of humanity. A complex brain allows self-awareness, self-reflection, and beyond that, an awareness and ability to reach out to a world of values with possibilities to live. Through their cognitive and emotive abilities, human beings are aware of their condition of vulnerability, finality, and mortality. They are the only species in creation with the capacity to take a stand and choose how they face suffering.

There are two critical windows that bracket one’s lifespan: birth and death. Toward the end of the lifespan, physical and cognitive functions may, to a more or lesser degree, deteriorate. However, the essence of the person, their spirit remains intact. There is a possibility for the manifestation of the dynamics of the spirit towards meaning.

What most people who are close to death hold dear in their final months, weeks, or hours, shows what the dying can teach us about living. At the forefront are those realities that can never be taken away from a human being: truth, beauty, and goodness that they experienced, and they brought into the word, and genuine connections they encountered and can still encounter until their final moments.

Frankl described what the human being is: A human being is a fundamentally meaning seeking and deciding being, who possesses the capacity to decide who he or she will become in the next moment.

Dame Cecily Saunders demonstrated why both care and comfort are relevant in palliative care: they allow us to optimize the search for meaning in the last stages of life, which belongs to human dignity.

Building a society that provides evidence-based, compassionate care and comfort at every stage of life, especially when human beings are most vulnerable, such as the end of life, is a sign of respect for humanity.

Special thanks to Prof. Dr. Christopher S. E. Wurm, MB BS FRACGP FAChAM, Senior Consultant in Primary Care, CALHN Integrated Care and Visiting Fellow, Discipline of Psychiatry, University of Adelaide, for his invaluable support in the preparation of this manuscript and sharing the documents pertaining to his correspondence with Dame Cicely Saunders, reproduced here with his permission.

References:

- Lasco, G. (2022). Did Margaret Mead Think a Healed Femur Was the Earliest Sign of Civilization? An anthropologist digs into the origins of a popular story attributed to Margaret Mead about the original sign of civilization. Entanglements. Retrieved from: https://www.sapiens.org/culture/margaret-mead-femur/ Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Saunders, C. (2001). The evolution of palliative care. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2001 Sep; 94(9):430-432. Retrieved from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1282179/. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Gambert, S. R. (2011). Examining the Evolution of Hospice and Palliative Care. Consultant 360. Multidisciplinary Medical Information Network. Retrieved from: https://www.consultant360.com/articles/examining-evolution-hospice-and-palliative-care. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Hospice Society of Camrose and District (2026). History of Hospice. Retrieved from: https://www.camrosehospice.org/history-of-hospice. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Tatum III, P. E., Craig, K. W., Washington, K. T., & Oliver, D. P. (2014). Getting Comfortable with Death: Evolution of the Care of the Dying Patient. Missouri Medicine. Mo Med. 2014 Jul-Aug; 111(4):298-303. Retrieved from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6179468/. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Neumann, C. E. (2023). Military Medicine on the Battlefield. EBSCO. Retrieved from: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/health-and-medicine/military-medicine-battlefield. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Black, W. (2023). Medicine and Miracle in a Medieval Monastery. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved from: https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2023/01/05/medicine-and-miracle-in-a-medieval-monastery/. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Bernard, I. (2020). In the secrets of the Hospices de Beaune. Retrieved from: https://www.france.fr/en/article/hospices-beaune/. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Verschuur, M. (2023). The History of the Hospice. Cortes Island DeathCare Collective. Retrieved from: https://islanddeathcare.ca/2023/03/31/the-history-of-hospice/ Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Reymond, S. (2026). L’oeuvre des dames du calvaire : Charite, dévotion et élitisme à Lyon au XIXe siėcle. Retrieved from : Open Edition Journals. https://journals.openedition.org/ch/443?lang=en#:~:text=Calvary%20Hospital. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Our Lady’s Hospice Limited (2026). Mission Statement. Retrieved from:https://olh.ie/about-us/mission-values/. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Redwine, H. M. & Ganti, L. (2024). Dame Cicely Saunders: Pioneering Palliative Care and the Evolution of Hospice Services. PubMed. NIH. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39759695/. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Kings College London (2026). Dame Cicely Saunders: A palliative care pioneer. Cicely Saunders Institute of Palliative Care, Policy and Rehabilitation. Retrieved from: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/cicelysaunders/about-us/cicely-saunders#:~:text. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Eissler, K. (1955). The Psychiatrist and the Dying Patient. New York, NY: International University Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1967). Psychotherapy and Existentialism. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Metzger, G. U. (2023). A shelter from the abyss: exploring Cicely Saunders’ vision for hospice care through the concept of worldview. Palliative Care Soc Pract. 2023 Mar 31;17. Retrieved from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10068131/. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Frankl, V. E. (2000). Recollections. An autobiography. Cambridge, MA: Perseus.

- Frankl, V. E. (2014). Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1994). Logotherapie und Existenzanalyse. Texte aus Sechs Jahrzehnten. Munich : Quintessenz.

- Marshall, M. & Marshall, E. (2021). Care and Consolation. The Doctor Who Saved Lives. Ottawa Institute of Logotherapy.

- Viktor Frankl Institute Vienna (2026). Legacy. Retrieved from: https://www.viktorfrankl.org. Accessed: January 8, 2026,

- NIH Library of Medicine (2005). Dame Cicely Saunders. Retrieved from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1179787/ Accessed: January 7, 2026.

- National Alliance for Care at Home (2026). Hospice Care. Retrieved from: https://www.caringinfo.org/types-of-care/hospice-care. Accessed: January 7, 2026.

- Cicely Saunders International (2026). Turning Point. Retrieved from: https://cicelysaundersinternational.org/dame-cicely-saunders-a-brothers-story/turning-point/ Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Viktor Frankl Institute Vienna (2026). Viktor Frankl Award. Retrieved from: https://www.viktorfrankl.org/vf_awardE.html. Accessed: January 7, 2026.

- Clark, D. (2014). Cicely Saunders, the 1960s and the USA. University of Glasgow, End of Life Studies. Retrieved from: http://endoflifestudies.academicblogs.co.uk/ Accessed: January 7, 2026.

- Saunders, C. (1988). Spiritual Pain. Journal of Palliative Care 4:3, 29-32. Retrieved from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/082585978800400306 Accessed: January 9, 2026

- Bell, U. M. (2019-2025). What Gives My Life Meaning? Logotherapy and Existential Analysis. Retrieved from: https://www.ursulamariabell.com/ Accessed: January 7, 2026.

- Saunders, C. (2003). Watch with me: An inspiration for a life in hospice care. Lancaster: Observatory Publications.

- Saunders, C. (2006). Dimensions of Death. In: Saunders, C, Clark, D. (Eds.) Cicely Saunders: Selected Writings 1958-2004. Oxford. Oxford University Press. Pages 1-4.

- Frankl, V. E. (2020). Yes to Life In Spite of Everything. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Viktor Frankl Institute (2026). Ten Theses on the Person. Retrieved from: https://www.viktorfrankl.org. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Frankl, V. E. (1951). Logos und Existenz. Vienna: Amandus Verlag.

- Saunders, C. (1987). What’s in a name? Palliat Med 1987; 1:57-61. Frankl, V. E. (1950). Homo Patiens. Vienna, Deuticke.

- Saunders, C. (1972). A therapeutic community: St. Christopher’s Hospice In: Schoenberg B, Carr AC, Peretz, D, et al. (eds.) Psychosocial aspects of terminal care. New York: Columbia University Press, 1972, 275-89.

- Saunders, C. (1965). The last stages of life. Am J Nurs 1965; 65:70-75. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3453113. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Phillips, D. (2025). Balfour Mount (1939-2025). Palliative Care McGill University. Retrieved from: https://www.mcgill.ca/palliativecare/about/portraits/balfour-mount. Accessed: January 8, 2026.

- Yorkin-Drazen (2002). Frankl’s Choice. A Documentary on the life and philosophy on the Viennese psychiatrist and philosopher, Viktor Frankl, MD, PhD. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0391161/

- Schwartz, S. (2025). Obituary: Palliative-care pioneer died at Royal Victoria unit named in his honour. Montreal Gazette, October 6, 2025. Retrieved from: https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/obituary-royal-vic-pioneer-dr-balfour-mount-was-north-americas-father-of-palliative-care

- Saunders, Cicely, ‘Spiritual Pain: First published in Journal of Palliative Care, vol. 4, no. 3 (1988), pp. 29–32.’, In: Saunders, C, Clark, D. (Eds.) Cicely Saunders: Selected Writings 1958-2004. Oxford. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198570530.003.0032, Accessed: January 9, 2026.

- Chi, L. (2013). An Evening with Ian Maddocks. Palliverse. Retrieved from: palliverse.com. Accessed: January 7, 2026.

- Wurm, C. S. E. (1992). Logotherapy in Palliative Care. Hospress 6(1):4-5.

- Saunders, C. (1992). Letter to Dr. Christopher Wurm. Private Communication. Shared with permission from Dr. Wurm.

- Saunders, C. (1991). Spiritual Pain. Contact. The Hospice Movement. No 122, October 1991, Pages 6-9. Shared with permission from Dr. Wurm.

- Saunders, C. (2019). Hospizwissen, heft 3/2019.

- St. Christopher’s Hospice (2026). St. Christopher’s. Retrieved from: https://www.stchristophers.org.uk/ Accessed: January 9, 2026

- Cicely Saunders Institute (2026). Cicely Saunders Institute of Palliative Care, Policy & Rehabilitation. Kings College, London. Retrieved from: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/ Accessed: January 9, 2026.

- Cicely Saunders International (2026). CSI. Retrieved from: https://cicelysaundersinternational.org/ Accessed: January 9, 2026.

- Lopez-Sola, M., Koban, L., Wager, T.D., (2019). Transforming pain with prosocial meaning; an fMRI study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 2018 Nov-Dec;80(9):814–825. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000609. Retrieved from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6218300/

- Wang, S., Xu, W., Zhu, Y., Zheng, M., & Wan, H. (2024). Effectiveness of meaning in life intervention programme in young and middle-aged cancer patients: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ open, 14(10), e082092. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-082092

- Haughan, G. & Dezutter, J., 2021. Meaning in Life: A Vital Salutogenic Resource for Health. In: Health Promotion in Health Care—Vital Theories and Research. Haughan, G. & Eriksson, M. (Eds.). Cham. Springer. 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585665/

- Batthyàny, A. & Guttmann, D. (2006). Empirical research on logotherapy and meaning-oriented psychotherapy. An Annotated Bibliography. Phoenix, AZ: Zeig, Tucker, and Theisen.

- Breitbart, W. (2017a). Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy in the Cancer Setting. Finding Meaning and Hope in the Face of Suffering. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Breitbart, W. (2017b). Meaning-centered Psychotherapy in the Cancer Setting. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Breitbart, W., Pessin, H., Rosenfeld, B., et al. (2018). Individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for the treatment of psychological and existential distress: a randomised controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer, 124, 3231-3239. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29757459/

- Breitbart, W. & Poppito, S. (2014a). Individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. A treatment manual. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Breitbart, W. & Poppito, S. (2014b). Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. A treatment manual. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Cohen, S. R. Mount, B. M., Thomas, J. J., and Mount, L. F. (1996). Existential well-being is an important determinant of quality of life. Evidence from the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire. Cancer, 77(3), 576-86. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8630968/

- Fillion, L. Dupuis, R., Tremblay, I., DeGrace, G-R., & Breitbart, W. (2006). Enhancing meaning in palliative care practice: A meaning-centered intervention to promote job satisfaction. Palliative and Supportive Care, 4, 333-344. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17133893/

- Fillion, L., Saint-Laurent, L., Dupuis, R. & Tremblay, I. (2007). La gratification liée à la pratique en soins palliatifs : témoignages d’infirmières. Les cahiers francophones de soins palliatifs. 7(2) 65-83. https://michel-sarrazin.ca/msarrazin/data/files

- Marshall, M. & Marshall, E. (2023). Viktor E. Frankl’s Logotherapy and Existential Analysis: Theory and Practice. Ottawa, ON: Ottawa Institute of Logotherapy.