Maria Marshall, PhD, RP

“…If we wanted to build a bridge from person to person—and this also applies to a bridge of recognition and understanding–the bridgeheads must not be the heads, but the hearts” (Frankl, 1992:162).

Fear and trust are fundamental human phenomena that exist on a continuum of psychological and physiological states with existential aspects. The dimension of spirit offers a dimension in which fear and trust can dialogue and can be reconciled for harmonious living. Neuroplasticity, based on discernment and reflection, can aid to reinforce values that we want to live for and that are in harmony with universal values. Through the resources of the human spirit, fear can be tamed, and basic trust can be re-gained for a meaning-filled living to avoid despair. Meaning is associated with self-transcendence, resilience, and post-traumatic growth. Meaningful living is related to positive health and mental health outcomes. In the light of these considerations, the journey from fear to trust is that of hope and faith—a living project—that unfolds in the context of Frankl’s three-dimensional view of the person, inspired, and guided by the unconditional trust in ultimate meaning and unconditional faith in ultimate being.

Introduction:

Dr. Viktor E. Frankl, MD, PhD (1905-1997), was a neurologist, psychiatrist, and the founder of Logotherapy and Existential analysis, a meaning-oriented approach to psychotherapy. One his great contribution to medicine was the re-humanization of psychiatry and psychotherapy though a three-dimensional view of the person, in which the body and mind are vulnerable and instruments of the spirit, and where the spirit is a non-material dynamic, and the essence of the person and his or her indestructible core. The articles that are explored in this presentation inform us of the dynamics of the body and the mind as the instruments of the spirit. It is meaningful to understand the processes of our body (1) to be able to appreciate the marvel of creation, (2) to accept and understand how we can best manage our emotions, (3) to gain insight of our area of freedom and fate; and (4) to understand how we can best take care of ourselves to be able to accomplish our mission; and (4) to reach out to others with hope. Thus, our trajectory will cover elements of self-discovery, self-distancing, and self-transcendence.

Therefore, the premise of this exploration is that, although we are conditioned, we are not determined:

In “The Will to Meaning” Frankl asserted that “…human beings are not fully conditioned and determined but they determine themselves whether to give in to these conditions or stand up to them. In other words, human beings are ultimately self-determined” (Frankl, 2014b:122).

The objectives of this research are: (1) to explore the bio-psychological mechanisms underlying fear and trust, (2) examine existential phenomena related to fear and trust, and (3) consider the ways in which meaning-orientation can foster trust to avoid despair.

Sources:

The sources of the present research are books of Prof. Viktor E. Frankl, MD, PhD. Additional resources were collected from books of logotherapists disseminating Frankl’s work, such as Prof. Elisabeth Lukas, PhD, and several other prominent experts in the field, books by the author on logotherapy and related topics, and research articles in the field of medicine, neurology, psychiatry, psychology, and counseling. The findings are examined in the context of a holistic view of the person as a body, mind, and spirit entity.

Fear:

Fear is one of our fundamental emotions. Other emotions include anger, disgust, sadness, surprize, and happiness (Gu, et al., 2019).

According to neuroscientific findings, four basic emotions, happiness, fear, sadness, and anger are differentially associated with three core affects: reward (happiness); punishment (sadness); and stress (fear and anger): “…These core affects are analogous to three primary colors (red, yellow, and blue) in that that are combined in various proportions to result in more complex ‘higher order emotions,’ such as love and esthetic emotion” (Gu, et al., 2019).

Often, we tend to categorize these emotions into positives and negatives. We aim for happiness, and maybe even surprize, and wish to avoid fear, disgust, sadness, and anger. This is a natural inclination. However, in excessively doing so, we may overlook the evolutionary value of emotions that serve the preservation of our lives. Realistic fear serves to protect us from danger. Lack of reasonable fear would lead to hotheaded actions. Excessive fear is unproductive because it blocks us down. Thus, the right management of fear ensures that we can use the energy of fear for our advantage.

The Neuropsychology of Fear

Emotions are part of pour psychological processes, closely linked with our physiological functioning. Brain regions involved in the generation and modulation of the fear response are complex and involve the recognition of danger through the hippocampus (the parahyppocampal gyrus), and the activation of the cerebellum-amygdala-cortical pathway. Cortical and sub-cortical regions help to interpret, modulate, and process our perception of fear, and activate our physical response to it (Javanbankht, & Saab, 2017).

It is interesting to note that the perception of fear occurs first unconsciously and then consciously. Within 100 ms after a stimulus is presented, there is an unconscious registering of it, and in about 400 ms it is registered consciously. Processing may take a long time after the event occurred (Williams, 2004).

The sympathetic nervous system is activated in response to the threat (Le Doux and Pine, 2016). At the neuro-physical level, processing fearful stimuli is associated with enhanced skin conductance, increased eye blink frequency, increased pupil dilation, and accelerated heart rate which indicate autonomic arousal to prepare the body to deal with the impending events (Tao, et al. 2021).

Figure 1: Routley, N. (2021). A Visual Guide to Emotion. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/a-visual-guide-to-human-emotion/

Language allows to express the internal feeling to others. It allows us to communicate, to describe and to transmit the emotion after we become aware of it (Junto Institute, 2022). Self-awareness of feelings helps to identify internal experiences and tonalities in relation to thoughts and behaviors.

Figure 2: Junto Institute (2021). Wheeel of Emotions. A colorful illustratetion of nuances and intensities. A conceptual guide.

From neurophysiological studies we also know that intense emotions affect attention and memory. Optimal arousal levels and emotional involvement is associated with greater encoding and retention of information; however, intense stress is counterproductive to rational thinking, complex reasoning, decision making, and problem solving (Sandi & Pinelo-Nava, 2007).

According to the stress theory of Hans Selye, intense stress leads to the fight or flight response. Intense fear may also lead to being blocked and “paralyzed” in the body’s attempts to ward off the fear (Selye, 1973).

In the condition of prolonged toxic stress, that is unbuffered by mediating forces such as a source of safety, security and trust, the body’s resources become increasingly depleted and physical and emotional disorders can result from prolonged and intense states of arousal (Bucci, et al. 2016).

Unreasonable fear, and fear of fear, the anticipatory anxiety related to anxiety disorders has been described by several researchers (Kessler, et al., 2009).

Neuroplasticity and the brain’s remarkable ability to form new connections helps to mediate the effects of stress and fear in the nervous system (Cramer, et al., 2011).

Trust:

According to a psychological definition, trust is an emotional brain state (Thagard, 2018). It has been described as (1) a complex neural process that binds diverse representations into a semantic pointer that includes emotions; (2) a feeling of confidence and security; (3) an abstract mental attitude toward the proposition that someone is dependable; (4) a belief in the probability that someone will behave a certain way (Thagard, 2018).

The Neuropsychology of Trust:

According to neuroscientific findings, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and insula, and the amygdala, as well as the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex are involved in the mediation of trust. The structure of these brain regions has been found to be directly influenced by the grey matter volume and amygdala volume as a function of decision making and trust in others (Haas, et al. 2014).

Figure 3: Illustration of trust and distrust in the activation of brain regions involved.

According to the developmental theory of Erik Erikson, one of the main tasks of the early stages of life rom birth to 18 months of age is to develop a secure bond with a loving caregiver for the maintenance of trust. In the absence of a secure connection, there is a fear of abandonment. Erikson believed that children who learn to trust their caregivers in infancy are more likely to have a sense of safety and security in the world. They will form trusting relationships with others in their lives (Graves and Larkin, 2006).

Current research confirms that traumatic events reduce the amount of trust one experiences (Filkukova, et al., 2016, Dahlen, 2010, AFWI, 2019). However, one can learn to develop trust if one faces one’s fears (Hillebrand, 2021). Trust mediates the perception of threat. It alters people’s perception of themselves, and the world around them (Enjolras, et al, 2019; Filkukova, et al., 2016). From am individual to a global scale, reducing fear and enhancing trust has been described as the main precondition for enhancing social concern and peace-making (Wheeler and Booth, 2008).

It is important to note that trust can not be forced, commanded, or demanded because it is a choice to trust someone. One trusts someone with similar values easier than someone with dissimilar values. Here is an area were freedom where will, the ability to make decisions and choice are manifested. While tolerance toward others with dissimilar values is possible, and required for peaceful coexistence, value-impositions run contrary to harmony. Adopting values not in line with universal human values– such as the value of each life, or the dignity of the person–is not meaningful. Meaning is the objective reality of a value standing in relation to each person in their own unique situation that has to be discovered, and discerned through conscience (Frankl, 2014b). Conscience is a “meaning-organ” (Frankl, 2008) that helps to intuit and infer the meaning of the moment, the person, and situation specific meaning, that is related to what is the very best possible option represented by the actualization of a value in harmony with universal values culminating in “the value of values” –Ultimate Meaning (Frankl, 2000).

Fear and Trust in the context of Meaning

Originally, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs outlined five areas of human concern: (1) physiological needs, (2) safety needs, (3) love and belonging, (4) esteem needs, and (5) self-actualization. In 1960, following an exchange with Viktor Frankl, Maslow acknowledged that the main motivation of human behavior is the will to meaning and added it to his hierarchy of needs (Marshall & Marshall, 2022). Thus, while several concerns can be the object of our fear and confidence, it is within a higher and more encompassing dimension of the dimension of the human spirit where we can reconcile our fears and give space to trust.

When conceptualizing of a person as a three-dimensional entity of body, mind, and spirit, it is the spiritual domain where the search for meaning takes place and where there is a healthy tension between a person and the values that they wish to actualize. According to Frankl, body and mind are instruments of the human spirit, through which the spirit expresses itself.

The dimension of body is the reservoir of physical resources. It is a bio-physical organism that ensures our physical functioning and survival (Frankl, 2014b). The mind in Frankl’s theory is used to denote our psychological processes, such as perception, memory, cognition, thinking, and emotions (Frankl, 2014b).

The dimension of the spirit is conceptualized as dimension that is higher and more encompassing than the dimension of the body and mind, not a substance but dynamics, the seat of the will to meaning, the defiant power of the human spirit, conscience, and other healthy resources such as our capacity for self-distancing, self-transcendence, humor, love, gratitude, hope and faith (Marshall & Marshall, 2022). Psycho-physical parallel and psycho-noetic antagonism refers to the fact that while body and mind are vulnerable, spirit is a healthy resource that can not become ill (Frankl, 1994, Marshall & Marshall, 2020).

The implications of the nature of the body, mind and spirit led Frankl to conceptualize his first and second Creed. According to the Psychological Creed, the person can be disturbed but not destroyed; and (2) according to the Psychiatric Creed, behind the mask of disease, the spirit is still intact (Frankl, 1994:86, 96).

Emotions Point to Values:

The arousal of emotions, correlated with inner brain states and paralleled by physiological responses, is like an inner source of energy that informs us about our values, value-system, and value-hierarchy.

For example, we feel sadness about loosing a family member because we loved them. Grief and sadness follow from love and closeness, the experiential values and attitudinal values remain as a bond between us and our loved ones.

We may feel angry if we see someone tosses garbage in the park because we value taking care of nature and care about the good use of resources.

We feel disgusted and repulsed by the cowardly actions of a compulsive liar, because we value truth and justice.

Emotions are like inner signals that tell us when events and actions are in harmony with the values that we perceive through our conscience as what should be, could be, or ought to be.

From a holistic point of view, this inner signal system is something that we have rather than who we are, and it serves an important function to guide our lives, not like instincts and impulses, but as signals that we can choose to act on, we can choose to embrace, or choose our position in response to.

Any signal system is as good as effectively it functions, as much as we pay attention to it, and the way we interpret its meaning wisely. Similarly, to a traffic light, where red means stop, yellow means go and green means go, it would be foolish to ignore our “gut feeling” and speed up when we see the light turning from yellow to red.

From a logotherapeutic point of view, we are in the driver’s seat, not our impulses, emotions, or drives, and there is always a space between a stimulus, and a response. We have an area of inner freedom to decide how to respond to our circumstances: give in to fears or not; develop trust or choose not to develop it. Our mind and heart, the emotional and rational brain work together in discerning what is most meaningful in each situation.

Existential Aspects of Fear

There are phenomenological states that occur when the voice of conscience is ignored, repressed, or suppressed, the will to meaning is blocked, when one does not find meaning to fulfill, or when one’s usual ways of fulfilling meaning in life are no longer possible:

- Existential vacuum- is the feeling of inner emptiness, boredom, that results when one does not see meaning is life (Frankl, 2014; 2014b).

- Existential frustration-occurs when the will to meaning is blocked.

- Existential distress- occurs upon long standing existential frustration and vacuum that can lead to depression and despair, noogenic neurosis (Frankl, 2004).

- Existential struggle-occurs in the case of values transgressions (Marshall & Marshall, 2021).

- The concept of “Existential Angst” has been widely used by the existentialists to describe a long-standing sense of lack of meaning in life.

- The term “existential threat” has been used to refer to a feeling that one’s mere existence in jeopardy (used to refer to a fear of loss of values, loss of selfhood, or identity).

- “Existential risk” is defined as “risks that threaten the destruction of humanity’s long-term potential” (Bostrom, 2002).

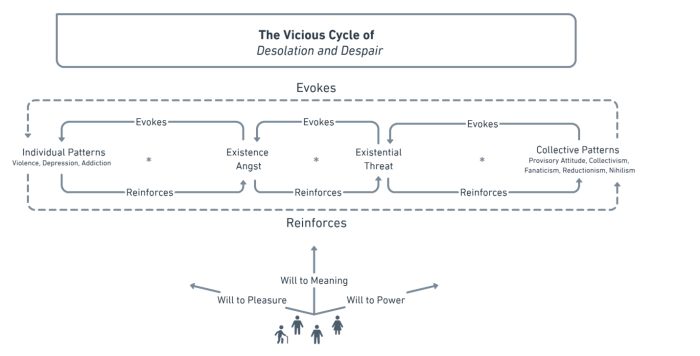

The Vicious Cycle of Fear of Fear Leading to Desperation

Frankl described that either avoiding or fighting fear increases fear and results in an anticipatory anxiety of fear of fear (Frankl, 2004). The same pattern can occur in groups and societies.

In the case of existential angst, the fear motivation can give rise to individual neurotic patterns: such as depression, aggression, and violence (Frankl, 2014b), especially when the will to meaning is frustrated, which further reinforces the existential angst.

In the case of existential threat, frustration of the will to meaning, can give rise to collective neurotic patterns, such as collectivistic thinking, fanaticism, reductionism, and nihilism, reinforcing the vicious cycle of existential threat and dread.

The common element between existential angst and existential threat is fear. How we respond to fear is therefore crucial in breaking the pattern blocking the will to meaning that leads to despair.

Figure 4: Maria Marshall (2022). Illustrates the vicious cycle of desolation and despair fuelled by fear.

Basic Trust

Erik Erikson talked about a fundamental trust that develops in early childhood and which can be easily lost and when one encounters trauma (Cherry, 2019). Frankl’s notion of trust is “…basic trust that is ultimately a belief in life’s meaningfulness which we can choose to embrace. Among other things, it means the awareness of our uniqueness and irreplaceable singularity as well as our value for the world” (Schechner & Zürner, 2011: 151). Basic trust is based on a choice “that life is ultimately meaningful” as opposed to “meaningless.” The loss of this ultimate trust leads to over-dependence on success, happiness, power and feedback about one’s value and the seeking of approval from others, seeking experiences, expectations that create an insatiable uneasiness and restlessness—the existential angst.

The opposite of existential angst is basic trust (Schechner & Zürner, 2011). Basic trust brings about an inner recognition and change of heart and mind to be free from the approval of the world and of others and to be self-determined, free, and responsible in the pursuit of meaning. Basic trust is opposed to “anxiety motivation” and avoidance with “love motivation” and intention toward purposeful goals (Lukas, 2020). Embracing this basic trust implies that we are wanted in the world. We are loved and a precious and irreplaceable part of creation. Inherent to this viewpoint is to appreciate what is good, true, and beautiful and gratitude for the wonders of life and creation. Basic trust can be fostered by: (1) Opening our eyes to possibilities: the ability to do good; the invitation to experience something beautiful and the capacity to transform suffering into something meaningful; (2) By awakening to the wonder and gift of every moment; (3) Through gratitude and kindness; (4) Through formation and personal development; (5) Through nurturing healthy relationships (6) Though a willingness to be open to the wonders of the world and changes in ourselves through gaining new experiences and insights (Schechner & Zürner, 2011).

According to Frankl (2019), an affirmation of life’s meaningfulness, or the possibility of life’s meaningfulness points to the possibility of a world in which every person is awaited and wanted and every person in addressed by life. Thus, in a world in which every person has value and dignity. This trust is the wellspring of hope that is strong enough to attract the energy of fear to use it to boost a person’s determination to jump over his or her own shadows or overcome obstacles and to thus channel the energy of fear into a meaningful action. Fabry (2021) outlined six ways in which basic trust can be furthered through orientation to meaning. He termed them the “signposts to meaning:” (1) uniqueness; (2) choices; (3) self-distancing; (4) self-transcendence; (5) responsibility and (6) response-ability. Attentive Meaning Sensitivity is a competence that can be practiced and enhanced (Marshall & Marshall, 2016).

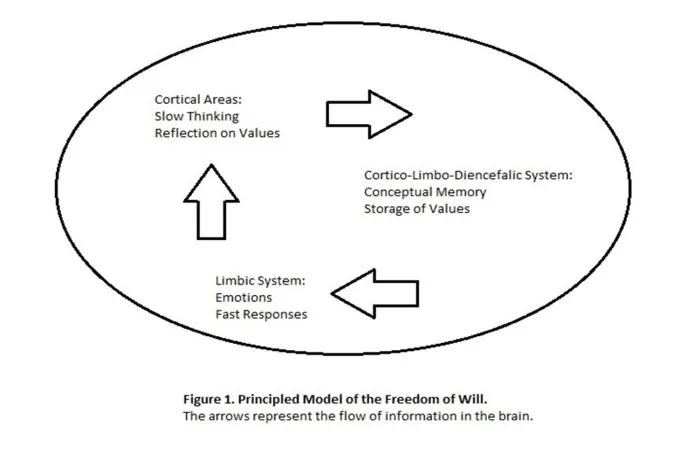

The Principled Model of the Freedom of Will

Within this framework, and consistent with a thorough review of the literature and neuroscience findings, the authors (Marshall & Marshall, 2017) put forth what they termed the Principled Model of the Freedom of Will (PMFW). This model shows that through a process of reflection, human beings can make decisions about which values to live for (slow process related to cortical brain activity associated with reasoning). These values are then stored in conceptual memory regulated by the cortico-limbo-diencephalic system to guide everyday decisions (fast process involving limbic structures associated with emotions).

Figure 5: Marshall, E. (2017). The Principled Model of the Freedom of Will.

Following the PMFW model, individuals can be helped to gain insight into their values as guiding principles. Individuals can affirm if they wish to live according to these values or choose other values in harmony with universal values.

“Freedom of the will is opposed to destiny. For what we call destiny is that which is essentially exempt from human freedom, that which lies neither within the scope of man’s power nor his responsibility. However, we must never forget that all human freedom is contingent upon destiny to the extent that it can unfold only within destiny and by working upon it” (Frankl, 1986:78).

Aside from many other factors, our brain physiology is part of our destiny because it is part of what has been given and made available to us. However, beyond mere brain functioning or destiny in life, or Providence, gifted each human being with a design that allows to creatively shape themselves to reach their ultimate destination.

Or, as Frankl stated, we may not be free from conditions, but we are free to bring something valuable into the world. Human beings can choose the values they wish to actualize and shape and mold themselves.

Self-Transcendence and Functional Brain Imaging:

A team of psychologists and experts in the field of mindfulness, Kristin Neff, Christopher Germer, Geshe Lobsang, Tenzin Negi, Christopher Willard, Jack Cornfield, Dennis Tirch, Susan Pollak, Paul Gilbert, Deborah Lee, and Laura Silberstein-Tirch with the National Institute for the Behavioral Application of Behavioral Medicine suggest that complementing traditional cognitive approaches with compassion practices is uniquely suited for addressing complex trauma (NICABM, 2019). The researchers differentiate between rumination “a repetitive thinking which focuses on negative internal states, self-perceptions and emotions” is associated with “increased levels of self-attention, personal distress, negative affect and poorer levels of autonomy and social and interpersonal functioning” (Sutton, 2016). They point out that reflection and meditation differ from rumination as their goal is to be open to a variety of experiences. They can involve observing the self-experience with the intention of gaining increased objectivity from different perspectives, angles, views, and contexts. They open access to bring unconscious resources to conscious awareness and open a pathway to strengths and resources. These researchers believe that, on a neurological level, people who engage in compassion are more likely to down regulate the arousal as it changes the tome of their setting from a simply cognitive exercise to being able to see an area of freedom where they can tale a stand toward themselves and events (NICABM, 2019). These psychologists have found that individuals who engage in compassion-oriented practices are able to better address early childhood issues than people who receive only traditional forms of therapy. By activating human compassion through action and relation to oneself and others, these individuals are more likely to experience fewer PTSD symptoms, score lower depression related measures, report lower levels of loneliness and sleep difficulties. They score higher on measures of happiness and sense of purpose. According to these psychologists, compassion is not just about being kind to your self and accepting yourself but being courageous and doing things differently. The core of it is to be able to do things for others. The most important aspect of compassion is the courage to do good to others (NICABM, 2019).

A large study by Yoona Kang and her colleagues (2018) was undertaken as a collaboration between schools of communication, departments of medicine, public health and neuroscience. The study explored whether affirmation and self-transcendent attitudes have the potential of affecting brain and eventually alter behaviour and health outcomes. Two hundred and twenty sedentary adults were randomly selected into two groups. Both group members received regular health programming and reminders about the benefits and advantages of healthy lifestyle, healthy nutrition and regular exercise. Participants in both groups were given a list of values to rank the order from highest to lowest personal significance. The control group was subsequently asked to engage in reflecting about those values which they deemed least significant to them along with everyday activities.

The other group participated in affirmation and compassion meditation. They were invited to reflect on the way they practice and experience their highest personally important values in their everyday lives. Subsequently, they practiced compassion meditation and well wishes in relation to these values and individuals. On the list the highest rated values included family members and connection with a transcendental entity.

Brain areas related to neural activity while performing these tasks were scanned and compared. Participants were also administered a battery of screening instruments related to their mood and health behaviours. Self-transcendence and compassion were found to significantly reduce the likelihood to evaluate the health messages as potentially threatening to the self esteem, even though beneficial (Kang et al, 2018). They predisposed participants for a tendency to openness, lowered defensiveness and valuing the health messages as “valuable to me.” Aside from message receptivity, there was an overall significant difference in mood and health behaviour. Self-directed, negative mood was less in the self-transcendence and compassion group than in the control group. Those who were affirmed showed greater increases in their average moderate/vigorous activity and decrease in sedentary behavior than those in the control group. Self-transcendent tasks stimulated the ventromedial prefrontal cortex associated with positive valuation and reward processing. During subsequent health message exposure, the same regions showed increased activity, indicating that affirmation, the reflection on values is interpreted as rewarding experience and coupled with self-transcendence, has the capacity to affect behavioural change (Kang et al, 2018).

These findings further support the idea that a positive, other focused mindset, characterised by kindness, compassion, gratitude and valuation may contribute to helping people see personally relevant information as valuable to them and they are more likely to engage in positive, healthy behaviours such as self care if they see a personal value and purpose attached to it. An interesting observation during this study was that even those who were asked to think about their values but reflected on lower ranked values showed some improvement in subsequent health related behaviours and showed pre-frontal activation, albeit not as much as the other group. This finding indicates that reflecting on one’s values, even if not followed by self-transcendent mindful and compassionate thinking, can have an affirmative effect (Kang, et al., 2018).

In fMRI images, Kang and her colleagues (2018) found frontal area activation during compassion and affirmation tasks related to self-transcendence and reflection of values that one wants to live for. The same frontal area activation was not found in the control group, who were asked to reflect on everyday activities.

Figure 6: (Kang et al., 2018.) Functional MRI images of the brain areas activated during affirmation, and compassion in comparison with the control group.

Brain Plasticity and Resilience:

Robust studies investigated the effects of early trauma on the developing brain and the effects of toxic stress on health and mental health outcomes in later adulthood (Harvard University, 2019). Brain-plasticity, the brain’s capacity to moderate the impact of trauma, develop new connections, has been observed during critical windows of development and during the life span. Toxic stress paired with a lack of supportive caregiving was linked with deficits in brain areas crucial to executive and control functioning in the social, cognitive, and emotional areas was noted (AFWI, 2019). Teaching internal self-regulation, problem solving, planning and organisation skills, cognitive flexibility, was found helpful to help override automatic responses and prevent reinforcing and transmitting adversity (Marshall & Marshall, 2021).

Miller Karas developed a Community Resiliency model that focuses on self-awareness and self-regulation to (1) track and understand bodily reactions, (2) access inner resources and learn how to evoke them and intensify them; (3) grounding, (4) understanding gestures and spontaneous movements; and (5) shift and stay, whereby one can intentionally recognize and down-regulate intense emotional states to reach an optimal level of physical and psychological arousal. This approach has been extensively used both nationally and internationally by the Trauma Resource Institute. It is appropriate for men, women, and children (Grabbe & Miller- Karas, 2017).

Building resilience skills and engaging in self-transcendent actions following trauma and complex PTSD was related to enhanced sense of meaning in life and post-traumatic growth in veterans. Engaging in meaningful community activities was perceived as qualities of “super-survivors” who not only overcame their trauma but helped others. Helping others, in return, was reported to have had a positive impact on the individual’s recovery following trauma (Southwick & Charney, 2018; Marshall & Marshall, 2021b).

Meaning in Life and Health Outcomes

A study with 1,546 individuals over the age of fifty found that in the presence of medium to severe pre-existing coronary heart disease at the baseline, purpose in life was associated with lower odds of having a myocardial infraction during a two-year follow up (Kim, 2015). A similar study with close to 7000 individuals found that those with higher purpose scores showed reduced likelihood of a cerebrovascular incident in the next four year-period (Kim, 2013). large study by Alimujaing and her colleagues (2019) in close to 7000 adults aged fifty years and over in the United States confirmed that stronger purpose in life was associated with lower all-cause mortality. These results were in line with findings by Koizumi, and his colleagues, according to which strong purpose was associated with 72 percent lower rate of death from stroke, a 44 percent reduction of the rate of chance of dying from a cardiovascular disease and overall 48 percent chance of dying from any cause of death in a population of men over the period of a thirteen year follow up, even if controlled for the effects of controlled stress and cardiovascular predisposing risk factors (Koizumi, et al., 2008).

The work of Patricia Boyle and her colleagues with 1151 elderly individuals at the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center (Boyle, et al., 2010) indicated that purpose in life was a protective factor against the development and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Autopsy results obtained post-mortem confirmed that those individuals who had higher purpose scores have shown less cognitive decline despite the presence of high burdens of Alzheimer related protein accumulation, as measured in the amount of beta-amyloid and tau deposits associated with the disease (Boyle, et al., 2012).

A longitudinal study in the United States by Case and Deaton (2015) found that in a population of 100,000 white men who were followed between 2000 and 2020, there was a dramatic increase of deaths due to suicide, drug and alcohol poisoning, and chronic illness due to drug or alcohol use between 2005 and 2020. They termed these factors as “death due to despair.”

Chen et al. (2020) who investigated “death due to despair” in a sample of 100,000 health care workers in the US, (66,492) females (between 2001 and 2017), and 43,141 males (1988-2014), found that people who had a deep-seated spirituality and religiosity and attended religious service at least once a week had significantly lower rates of death related to suicide or addictions and overdose than those who did not have religious church attendance. Church attendance was positively correlated with psychosocial well-being outcomes, greater purpose in life and social integration.

A review of purpose and health-related studies was conducted by Dr. Adam Kaplin, chief psychiatric consultant to the Johns Hopkins Multiple Sclerosis and Transverse Myelitis centres and Laura Anzaldi (Kaplin & Anzaldi, 2015). Their observation is that research on the role of purpose is a new and upcoming movement in neuroscience. Considering the several side effects of pharmaco-therapy, especially in the areas of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, these authors believe that “purpose in life should be promoted, as opposed to pill-pushing.” In other words, methods that enhance a sense of purpose and meaningfulness in life are desperately called for to complement current clinical practices.

Several recent studies shed further light on wishes for hastened death in people diagnosed with terminal cancer and the elderly. The following points summarize the findings:

- Death wishes [in older adults] can not be explained by mental disorders (Van Wijngaarden, et al, 2021).

- The mental health consequences of isolation are disconnection, meaninglessness, anxiety, panic, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, digestive problems, depressive problems, and post-traumatic stress (Rogers, et al., 2020; Pietrabissa & Simpson, 2020) and psychiatric symptoms (Brooks et al., 2020).

- The trajectories of death wishes can be varied and fluctuate (Breitbart, 2017; Leigh, et al., 2017).

- Active, outspoken, and expressed wishes can subside and vanish over the months or years (Van Wijngaarden, et al., 2021)

- Wishes for hastened death are related to external factors such as health, activities, and relationships (Van Wijngaarden, et al, 2021).

- Once the desires are firmly established, and in the absence of support, these wishes can be enduring (Wilson, et al., 2007).

- Diminished wish for hastened death is linked with a regained sense of meaningfulness and forming connectedness (Breitbart, 2017; Southwick & Southwick, 2020; Van Wijngaarden, et al. 2021).

A ground-breaking study validated with randomised control trials at the Sloan Kettering Cancer Treatment Hospital in New York under the direction of William Breitbart outlined an eight session “Meaning-centered Group Psychotherapy Protocol; MCGP” (Breitbart, and Poppito, 2014a, Breitbart & Masterson, 2016; Breitbart, 2017). The sessions were intended to reduce anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation among patients who have been diagnosed with advanced stages of cancer and to increase their well being and quality of life by helping them find deeper meaning in the midst of battling their disease. They covered topics in eight consecutive sessions:

- Concepts and Sources of Meaning.

- Identity Before and After the Diagnosis of Cancer Diagnosis.

- Historical Sources of Meaning: “Life as a Legacy” that one has been given.

- Historical Sources of Meaning: “Life as Legacy” that one lives and will give.

- Attitudinal Sources of Meaning: Encountering Life’s Limitations.

- Creative Sources of Meaning: Creativity, Courage, and Responsibility.

- Experiential Sources of Meaning: Connecting with Life through Love, Beauty, and Humor.

- Transitions: Final Group Reflections and Hopes for the Future.

Those who completed the program showed lower scores on depressiveness, anxiety and wish for hastened death. Despite their cancer diagnosis, they reported higher levels of quality of life than people in the control group. The researchers noted that offering physical care is crucial in palliative medicine (Breitbart, 2017). Beyond that “…it is equally important to encourage the spirit by a constant show of love and compassion” (Kissane, and Poppito, 2006: 694), and enhance resilience though meaningful connections (Southwick & Southwick, 2020; Southwick & Charney, 2021).

In several studies, meaning was found to correlate with measures of self-transcendence, resilience, and post-traumatic growth, which are factors associated with psychological well being. Thus, meaning can be conceptualized as creating a bridge between protective factors in the face of adversity and directly contributes to psychological well-being (Russo-Netzer, & Ameli, 2021).

Based on current criteria for evidence-based research, Lewis (2014) summarized the findings of studies to date: (1) A positive correlation exists between meaning and measures of well-being and coping: (2) An inverse correlation exists between meaning and a diagnosis of mental illness; (3) When mental illness does occur, an inverse correlation exists between meaning and symptom severity. Other well-documented findings are: (1) an inverse correlation exists between reasons for living, or purpose in life, and suicidality; (2) an inverse correlation exists between meaning and a diagnosis of substance use disorders; (3) a positive correlation exists between meaning and health. Emerging findings include: (1) meaning in life is positively correlated with occupational functioning; (2) an inverse correlation exists between meaning and criminal or antisocial behavior; (3) meaning in life is positively correlated with social functioning (Lewis, 2014).

Conclusion:

The present review of literature corroborates that neuroplasticity, based on discernment and reflection, can aid to reinforce values that we want to live for and that are in harmony with universal values. Through the resources of the human spirit, fear can be tamed, and basic trust can be re-gained for a meaning-filled living. Meaning is associated with self-transcendence, resilience, and post-traumatic growth. These factors are associated with positive health and mental health outcomes.

Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy and Existential Analysis was formulated at a time when the search for meaning was a crucial preventive and protective factor against despair. It is a values-based approach to psychotherapy and counselling with principles and evidence-based methods (Russo-Netzer & Ameli, 2021; Marshall & Marshall, 2022).

Perhaps only a few people are aware that Frankl was afraid of heights (Marshall & Marshall, 2021). He challenged himself to rock climbing: “Who is stronger. Me or the fear in me?” he used to ask (Frankl, 2008). With the fear he climbed, and he advised is patients to do the same. In brief, to “Take the bull by the horns!” (Lukas, 2000:105) and “Hitch your wagon to a star!” (Lukas, 2011).

However, Frankl did not scale the rocks unaided. He used proper mountain gear and a rope. One of such ropes is exhibited at the Viktor Frankl Museum in Vienna (Marshall & Marshall, 2021). A rope is a symbol of our connectedness to others, to the world, to hope and security and trust. The rope is the symbol of our connection to our ultimate home.

When we learn about logotherapy, we not only learn to help ourselves, but we also learn about a skilful way of guiding people from less difficult to most difficult terrains. The most challenging heights are the ones where we must jump over our shadows and turn the energy of our emotions to propel us to new heights. These heights can not be conquered other than with courage, faith, and trust.

Dr. Frankl affirmed that anchored in Ultimate Trust, we can say “Yes” to life, despite everything. He ended his book, the “Will to Meaning” with what he said that he intended to be “the lesson to learn” from this book (Frankl, 2014b:121):

“…Out of an unconditional trust in ultimate meaning and unconditional faith in ultimate being, Habakkuk chanted this triumphant hymn: ‘Although the fig tree will not blossom, neither shall fruit be in the vines; the labor of the olive shall fail, and the fields shall yield no meat; the flock shall be cut off from the fold, and there shall be no herd in the stalls: Yet I will rejoice in the Lord, I will be joyful in the God of my salvation” (Frankl, 2014b:121).

As Dr. Frankl taught lessons about life by the way he lived his life, and the way he practiced, we must also live what we believe. The “unconditional trust in ultimate meaning and unconditional faith in ultimate being” (Frankl, 2014b:121) can be our motto, our inspiration and hope on our journey from fear to trust. – A living project.

References:

Alimujiang A, Wiensch A, Boss J, et al. Association between life purpose and mortality among US adults older than 50 years. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5): e194270. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4270

AFWI (2019). Alberta family wellness initiative. Brain story certification course. Author. http://www.albertafamilywellness.org

Bostrom, N. (2002). Existential risks: Analyzing human extinction scenarios and related hazards” J of Evolution and Technology. 9 (1). http://www.nickbostrom.com

Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA (2010). Effect of purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons Arch Gen Psychiatry, 67(3), 304-310. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208

Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A.S., Wilson, S. R. (2012). Effect of purpose in life on the relation between Alzheimer Disease pathological changes on cognitive function in advanced age. Arch gen Psychiatry, 69(5):499-504. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1487.

Breitbart, W., and Masterson, M. (2016). “Meaning-centered psychotherapy in the oncological palliative care setting.” In: Clinical Perspectives on Meaning, P. Russo Netzer, S. Schulenberg and A. Batthyány (eds.). New York, NY: Springer International, 245-260. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/978-3-319-41397-6_12

Breitbart, W., and Poppito, S. (2014a). Individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. A treatment manual. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Breitbart, W. (2017). Meaning centered psychotherapy in the cancer setting. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., and Greenberg, N. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395, 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.

Bucci, M., Marques, S. S., Oh, D., Harris, B. (2016). Toxic stress in children and adolescents. Advances in Pediatrics, 63 (1), 403-428.

Case, A. & Deaton, A. (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. PNAS, 112(49) 15078-15083. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1518393112

Chen Y, Koh HK, Kawachi I, Botticelli M, VanderWeele TJ. Religious service attendance and deaths related to drugs, alcohol, and suicide among US health care professionals. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(7):737–744. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0175

Cramer, S. C., Sur, M., Dobkin, B. H., O’Brien, C., & Sanger, T. (2011). Harnessing neuroplasticity for clinical applications. Brain 134(6), 1591-1609.

Dahlen, H. G. (2010). Undone by fear? Deluded by trust? Midwifery, 26(2), 156-162. https://doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.midw.2009.11.008

Enjolras, B., Steen-Johnsen, K., Herreros, F., Bugge Solheim, O., Slagsvold Winsvold, M., Kushner Gadarian, M., and Oksanen. A. (2019) Does trust prevent fear in the aftermath of terrorist attacks? Perspectives on Terrorism 13, no. 4 (2019): 39–55 https://www.jstor.org/stable/26756702.

Fabry, J. (2021). Guideposts to meaning. Discovering what really matters. Charlottesville, VA: Purpose Research.

Filkukova, P., Hafsatd, G. S., & Jensen, T. K. (2016). Who can I trust? Extended fear during and after the Utøya terrorist attack. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, Vol 8(4), Jul 2016, 512-519.

Frankl, V. E. (1986). The doctor and the soul. New York, NY: Random House.

Frankl, V. E. (1992). Psychotherapie fur den Alltag. Herder/Spektrum.

Frankl, V. E. (1994). Logotherapie und Existenzanayse. Texte aus sechs Jahrzehnten. München: Quintessenz.

Frankl, V. E. (2000). Man’s search for Ultimate Meaning. Cambridge, MA: Perseus.

Frankl, V. E. (2004). On the theory and therapy of mental disorders. Brunner/Routledge.

Frankl, V. E. (2008). Bergerlebnis und Sinnerfahrung. Innsbruck: Tyrolia.

Frankl, V. E. (2014). Man’s search for meaning. Boston, MA: Beacon Press

Frankl, V. E. (2014b). The will to meaning. New York, NY: Plume.

Frankl, V. E. (2019). Yes to life in spite of everything. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Grabbe, L.& Miller-Karas, E. (2017). The trauma resiliency model : A “bottom-up” intervention for trauma psychotherapy. J of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association., 24(1):76-84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390317745133.

Graves, S. B., & Larkin, E. (2006). Lessons from Erikson: A look at autonomy across the lifespan. J of Intergenerational Relationship 4(2). 61-71.

Gu, S., Wang, F., Patel, N. P., Burgeois, J. A., and Huang, J. (2019). A model for basic emotions using observations of behavior in drosophila. Front. Psychol., https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00781,

Haas, B. W., Isjak, A., Anderson, I. W., Filkowski, M. M. (2015). The tendency to trust is reflected in human brain structure. NeuroImage. Volume, 107:175-181.

Harvard University (2109). Child Development Core Story-Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Cambridge, MA: Author. https://developigchild.harvard.edu

Hillebrand, K. (2021). The role of fear and trust when disclosing personal data to promote public health in a pandemic crisis. In: Ahlemann, F., Schütte, R., Stieglitz, S. (eds) Innovation Through Information Systems. WI 2021. Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organisation, vol 46. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86790-4_18.

Junto Institute (2022). The Junto Emotion Wheel. http://www.thejuntoinstitute.com.

Javanbankht, A. & Saab, L. (2017). What happens in the brain when we feel fear? Science. Smithsonian Magazine. www.smithsonian.com

Kang, Y., Cooper, N., Pandey, P., Scholz, C., O’Donnell, M. B., Lieberman, M. D., Taylor, S. E., Strecher, V. J., Cin, S. D., Konrath, S., Polk, T. A., Resnickow, K., An, L., Falk, E. B. (2018). Effects of self-transcendence on neural responses to persuasive messages and health behavior change. PNAS, 155, 40, 9974-9979. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1805573115/-/DCSupplemental

Kaplin, A & Anzaldi L (2015). New movement in neuroscience: A purpose-driven life. Cerebrum, 7.

Kessler, R.C., Ruscio, A. M., Shear, K., & Wittchen, H-U. (2009). Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders. Behavioral neurobiology of anxiety and its treatment, 21-35.

Kim, E. (2015). Purpose in life and cardiovascular health. Doctoral Dissertation. [Retrieved from: deepblue.lib.umich.edu].

Kissane DW, and Poppito S. (2006). “Death, Dying and Bereavement.” In: Blumenfield M., Strain JJ, (eds.) Psychosomatic medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Koizumi M, Ito H, Kanko Y, Motohashi Y (2008). Effect of having a sense of purpose in life on the risk of death from cardiovascular diseases. J Epidemiol, 18(5), 191-196. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE2007388

Lewis M (2014). The logotherapy evidence base: A practitioner’s review. www.academia.edu

LeDoux, J. E., & Pine, D. S. (2016). Using neuroscience to help understand fear and anxiety: a Two-system framework. Am J Psychiatry, 173 (2016), pp. 1083-1093.

Leigh-Hunt, N., Bagguley, D., Bash, K., Turner, V., Turnbull, S., Valtorta, N., et al. (2017). An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 152, 157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035.

Lukas, E. (2000). Logotherapy textbook. Toronto: Liberty Press.

Lukas, E. (2011). Binde deinen Karren an einen Stern. Was un sim Leben weiterbringt. Neue Stadt.

Lukas, E. (2020). Wie Leben Gelingen Kann. Interview with Michael Ragg. EWTN Television. Translated by Maria Marshall. Unpublished Manuscript.

Luton, J. (2015). Braun structure varies depending on how trusting people are of others, study shows. UGA today. http://www.news.uga.edu.

Marshall E.& Marshall, M. (2017). Anthropological basis of meaning-centered therapy. Ottawa, Canada: Ottawa Institute of Logotherapy.

Marshall, M. & Marshall, E. (2016). Attentive: The competence to discern meaning. Ottawa, Canada: Ottawa Institute of Logotherapy.

Marshall E. & Marshall, M. (2021). Wellbeing through meaning. Burnout prevention for the helping professional. Ottawa, Canada: Ottawa Institute of Logotherapy.

Marshall, E.& Marshall, M. (2021b). Logotherapy and Existential Analysis for the management of moral injury. Ottawa, Canada: Ottawa Institute of Logotherapy.

Marshall, M. & Marshall, E. (2022). Viktor E. Frankl’s logotherapy and existential analysis. Theory and practice. Ottawa, Canada: Ottawa Institute of Logotherapy.

Marshall, M. & Marshall. E. (2021). The doctor who saved lives. Ottawa, Canada: Ottawa Institute of Logotherapy.

National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine (2019). Master Series of the Clinical Applications of Compassion. Storrs, CT: NICABM. http//www.niacbm.com/program/compassion].

Pietrabissa, G., & Simpson, S. G. (2020). Psychological consequences of social isolation during COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychol., 09 Sept 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02201

Rogers, J. P., Chesney, E., Oliver, D., Pollak, T. A., McGuire, P., Fusar-Poli, P., et al. (2020). Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 611–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0

Routley, N. (2021). A visual guide to emotion. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/a-visual-guide-to-human-emotion/

Russo-Netzer, P., and Ameli, M. (2021). Optimal sense-making and resilience in times of pandemic: integrating rationality and meaning in psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychology, Review. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645926

Sandi, C. & Pinelo-Nava, M. T. (2007). Stress and memory: behavioral effects and neurobiological mechanisms. Neural plasticity. https://doi.org/10.1155/2007/78970

Schechner, J. & Zürner, H. (2011). Krisen Bewältigen. Viktor E. Frankls 10 Thesen in der Praxis. Vienna, Autria: Braumuller.

Selye, H. (1973). The evolution of the stress concept: The originator of the concept traces its development from the discovery in 1936 of the alarm reaction to modern therapeutic applications. American Scientist 61(6), 692-699.

Southwick, S. M., Charney, D.S. (2018). Resilience: The science of mastering life’s great challenges (2nd Ed). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Southwick, S. & Charney, D. (2021). Resilience for frontline health care workers: Evidence based recommendations. The American J of Medicine, 134(7), 829-830.

Southwick, S. M., Lowther, B. T., and Graber, A. (2016). “Relevance and Applications of Logotherapy to Stress and Trauma.” In: Logotherapy and Existential Analysis: Proceedings of the Viktor Frankl Institute Vienna, Vol. 1, A. Batthyány (ed.). Vienna: Springer International, 131-149.

Southwick, S. M. & Southwick, F. S. (2020). The loss of social connectedness as a major contributor to physician burnout. Applying organizational and teamwork principles for prevention and recovery. JAMA Psychiatry, E1-E2.

Sutton A (2016). Measuring the effects of self-awareness: construction of the self-awareness outcomes questionnaire. Eur J Psychol, 12(4), 645-658. Doi: 10.5964/ejop.v12i4.1178 [Retrieved from: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov].

Tao, D., He, Z., Lin, Y., Liu, C., and Tao, Q. (2021). Where does fear originate in the brain? A coordinate-based meta-analysis of explicit and implicit processing. Elsevier. Neuroimaging. http://www.elsevier.com/locate/neuroimage

Van Wijngaarden, E., Merzel, M., Van der Berg, V., Zomers, M., Hartog, I., & Leget, C. (2021). Still ready to give up on life? A longitudinal phenomenological study into wishes to die among older adults. Social Science and Medicine. Vol. 284, September 2021, 114180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114180

Wheeler, N., & Booth, K. (2008). The security dilemma: Fear, cooperation, and trust in world politics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Willliams, L. M., Liddell, B. J., Rathjen, J., Brown, K. J., Gray, J., Phillips, M. Young, A., Gordon, E. J. b.m., (2004). Mapping the time course of unconscious and conscious perception of fear: an integration of central and peripheral measures, 21, 64-74.